The satellite monitoring site that never was

Was Alberta once considered for the location of a satellite monitoring site for CSE? That’s my current working hypothesis.

An access to information request I recently submitted to the Privy Council Office may eventually provide the evidence to confirm or reject that hypothesis — but only if Ottawa can transcend its reflex for pointless redactions.

During the 1980s, CSE undertook a major effort to modernize the Canadian SIGINT program. Among other initiatives, the agency revitalized its cryptanalytic capabilities, established intercept sites in Canadian diplomatic facilities, began monitoring commercial satellite (COMSAT) communications, and bolstered CSE’s staff by 50%. (You can read more about CSE’s 1980s renaissance here.)

Satellite communications were an increasingly important part of both government and non-government international telecommunications during the 1980s.

Commercial communications satellite services began in 1965, when an intergovernmental consortium called INTELSAT launched Early Bird, the first commercial communications satellite. Shortly thereafter, NSA and GCHQ set up the ECHELON program to monitor traffic of interest on INTELSAT’s satellites.

By the 1980s, the growing volume of communications carried by INTELSAT and other commercial and national satellite operators made it desirable to bring the other UKUSA partners into the program. In March 1987, Australia announced plans to construct a satellite monitoring station at Geraldton, Western Australia, and in December 1987, New Zealand announced that it would build a similar station at Waihopai.

For Canada, entry into the satellite monitoring program was understood as a means both of augmenting our contribution to the UKUSA partnership and of collecting intelligence of specific interest to the Canadian government.

Documents recently released to the Canadian Foreign Intelligence History Project (CFIHP) through the Access to Information Act confirm the broad outlines of the Canadian plan. These documents show that the satellite monitoring project was a key element of the renewal plan that CSE pitched to the Interdepartmental Committee on Security and Intelligence (ICSI) in March 1984 in its Strategic Overview of the Cryptologic Program, 1985-1988.

The Strategic Overview document itself is rather heavily redacted, but it does confirm that one of the projects CSE proposed is related to COMSAT collection, and a handwritten annotation notes that this project was approved.

Another document, an External Affairs memo from December 1987, is more revealing, confirming that “ECHELON is a CSE project which was designed to collect Intelsat communications…. Our position on ECHELON has been to support the project as a valuable contribution to the overall Canadian and allied effort.” At the time of that memo, the project was on hold due to legality concerns expressed by the Department of Justice. But those concerns appear to have been resolved not long afterwards, as 1988 documents confirm that the project was back on track. A June 1988 document notes, for example, that “PILGRIM and ECHELON are going forward.” (PILGRIM was the project to operate intercept sites in Canadian diplomatic facilities.) Another document, from March 1988, lists “possible options to address identified intelligence deficiencies," one of which is "greater exploitation of the ECHELON program to yield more Canada-specific information, while contributing to the allied SIGINT effort."

Canadian

Forces Station Leitrim, located just south of Ottawa, became the home of Canada's satellite monitoring effort.

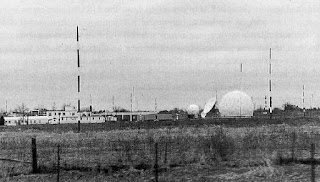

Air photos that the author has examined at the National Air Photo Library show that the first satellite monitoring dish was installed at Leitrim between late 1984 and early 1985. A second large dish was installed in 1985-86, followed by a third in 1987 and a fourth in 1989-90. A couple of small dishes were also in place by that time.

This 1988 photo, taken from Leitrim Road, shows the three main dishes then at Leitrim (two of them covered by radomes). A small dish can also be seen between the left-hand radome and the large uncovered dish.

Another site was proposed

The Strategic Overview document reveals, however, that Leitrim was not originally intended to be Canada’s primary satellite monitoring site. The fact that one or more new facilities were envisaged was redacted from the version released to the CFIHP, but a less redacted portion of the document tells the tale:

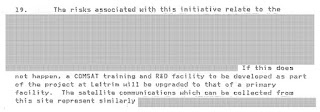

The risks associated with this initiative relate to the [redacted.] If this does not happen, a COMSAT training and R&D facility to be developed as part of the project at Leitrim will be upgraded to that of a primary facility. The satellite communications which can be collected from this site represent similarly [redacted.]

Another document released to CFIHP also confirms that “Should [redacted element of the plan] fail to happen, a training site planned for C.F.S. Leitrim will be developed into a full-fledged collection station”.

Where might CSE have wanted to monitor satellite communications originally?

Leitrim is in a good location to monitor the INTELSAT satellites stationed over the Atlantic Ocean, which carry communications between the Americas and Europe/Africa. It could also monitor many of the national satellites that serve parts of the Americas, such as Mexico’s Morelos satellites and Brazil’s Brazilsats, both of which systems were established in the 1980s. But it is too far east to monitor the INTELSAT satellites over the mid-Pacific.

Thus, CSE may have wanted to build a separate West Coast site from which to collect satellite traffic between Asia and North/South America. Or it may have sought a single site from which satellites over both the Atlantic and the Pacific — and everywhere in between — could be monitored.

Alberta bound?

Such a site would have been possible in southern Alberta, although the furthest east of the satellites over the Atlantic and the furthest west of the satellites over the Pacific would not be visible. (The arc of coverage would range from about 175-180 degrees east to 40-55 degrees west.)

Was such a site under consideration? Another document released to the CFIHP suggests it may have been.

The document is a list of intelligence-related files held by the Privy Council Office. Among other topics, the list contains several pages of CSE-related files, including two sets of files, both established in 1986, called “Collection Sites — Alberta”.

It is very unlikely that these files refer to radio collection sites. Canada hasn’t had a radio collection site in Alberta since the Canadian Army’s Grande Prairie site was closed in 1947, and I can’t imagine any reason why CSE would have considered opening a new radio collection site in the province in the 1980s. One of the main goals of CSE’s modernization project was to move the agency away from its overreliance on radio collection: the same year these files were opened the major radio collection site at Inuvik was closed.

Consideration of possible locations for a satellite monitoring site thus seems like a much more likely explanation for these files. In September I submitted an access to information request asking for the records in the files to be released. Now we wait to see what PCO and CSE will agree to release.

But why wait?

In the meantime, it’s fun to speculate as to where an Alberta satellite collection site might have been built had the plan gone ahead.

My wild ass guess is that Canadian Forces Base Suffield, the largest army training area in Canada, was CSE’s main candidate. Located about 50 km northwest of Medicine Hat, the 2,700-sq-km base also hosts DRDC Suffield (formerly called Defence Research Establishment Suffield).

Building the site at Suffield would have made the CSE station quite similar to NSA’s Yakima Research Station, one of the first ECHELON sites, which was located at the U.S. Army’s 1,300-sq-km Yakima Training Center in Washington state from 1974 until roughly 2013, when its functions were transferred to Buckley Air Force Base (now Buckley Space Force Base).

CSE may have hoped that if it built the site on a base like Suffield, its true purpose would go unnoticed. Like Yakima, Suffield would have provided a location big enough to keep the dishes largely away from prying eyes on land already owned by the Department of National Defence and with support services already available. Construction of the dishes could have been explained as communications research work associated with Defence Research Establishment Suffield, while the existing civilian and military workforce at the base would have enabled the mostly military intercept staff to hide in plain sight, at least potentially drawing much less attention than a newly constructed free-standing site would have.

The base was also well served by high-capacity telecommunications, being directly on the route of the Trans-Canada Microwave System.

So Suffield seems like a natural candidate.

As I said, however, this is all wild ass speculation. It may well be that Suffield was never under consideration. It could even be that the “Collection Sites — Alberta” files are unrelated to CSE’s satellite monitoring proposals.

As far as we know, no collection site of any kind has been built in Alberta since the 1940s. There is some reason to believe that in 1992 CSE investigated the possibility of building a separate satellite monitoring station in Ontario, at the former National Research Council radio observatory site at Lake Traverse, Algonquin Park. But nothing came of that either.

In the end, Leitrim became CSE’s primary satellite monitoring site, and it remains the primary site today. Documents confirm that INTELSAT monitoring associated with the ECHELON program went ahead, but it seems that it did so without the construction of a separate satellite monitoring site in Alberta or anywhere else.

Will PCO and CSE release any additional information that sheds light on what CSE proposed, what did and didn’t occur, and why these decisions were made some 35-40 years ago? That remains to be seen.